#China Mieville

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

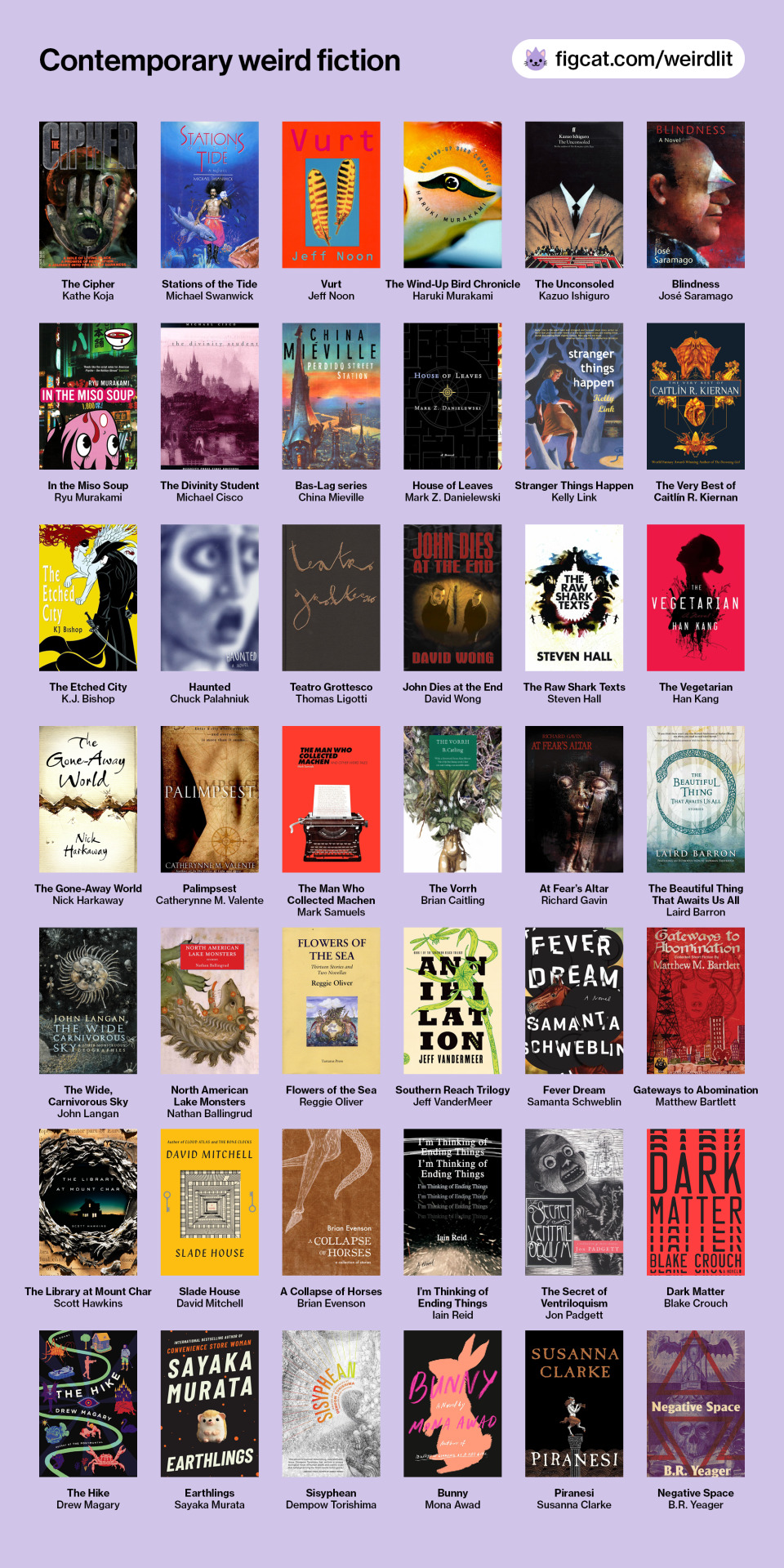

Contemporary weird fiction reading list

A chart of New Weird books and other bizarre, unsettling, and uncanny literature published in the last 30 years or so. This is a follow-up to my previous chart of classic weird fiction and another selection from my list of over 200 works of weird literature.

#book recs#book recommendations#book reccs#reading list#book list#literature#weird fiction#weird tales#weird books#the weird#new weird#jeff vandermeer#china mieville#haruki murakami#house of leaves#thomas ligotti#michael cisco#laird barron

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

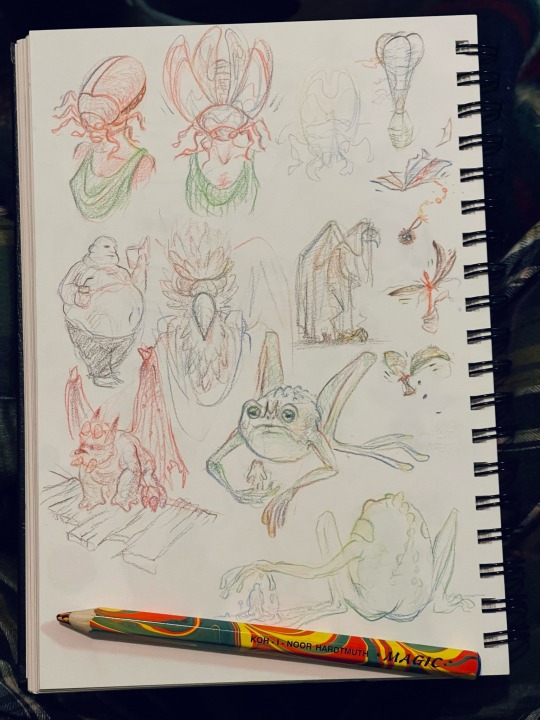

Haven't finished Perdido Street Station yet, but wanted to sketch Lin anyway

436 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theses on Monsters, China Mieville

1.

The history of all hitherto-existing societies is the history of monsters. Homo sapiens is a bringer-forth of monsters as reason’s dream. They are not pathologies but symptoms, diagnoses, glories, games, and terrors.

2.

To insist that an element of the impossible and fantastic is a sine qua non of monstrousness is not mere nerd hankering (though it is that too). Monsters must be creature forms and corpuscles of the unknowable, the bad numinous. A monster is somaticized sublime, delegate from a baleful pleroma. The telos of monstrous quiddity is godhead.

3.

There is a countervailing tendency in the monstrous corpus. It is evident in Pokémon’s injunction to “catch ’em all,” in the Monster Manual’s exhaustive taxonomies, in Hollywood’s fetishized “Monster Shot.” A thing so evasive of categories provokes—and surrenders to—ravenous desire for specificity, for an itemization of its impossible body, for a genealogy, for an illustration. The telos of monstrous quiddity is specimen.

4.

Ghosts are not monsters.

5.

It is pointed out, regularly and endlessly, that the word “monster” shares roots with “monstrum,” “monstrare,” “monere“—”that which teaches,” “to show,” “to warn.” This is true but no longer of any help at all, if it ever was.

6.

Epochs throw up the monsters they need. History can be written of monsters, and in them. We experience the conjunctions of certain werewolves and crisis-gnawed feudalism, of Cthulhu and rupturing modernity, of Frankenstein’s and Moreau’s made things and a variably troubled Enlightenment, of vampires and tediously everything, of zombies and mummies and aliens and golems/robots/clockwork constructs and their own anxieties. We pass also through the endless shifts of such monstrous germs and antigens into new wounds. All our moments are monstrous moments.

7.

Monsters demand decoding, but to be worthy of their own monstrosity, they avoid final capitulation to that demand. Monsters mean something, and/but they mean everything, and/but they are themselves and irreducible. They are too concretely fanged, toothed, scaled, fire-breathing, on the one hand, and too doorlike, polysemic, fecund, rebuking of closure, on the other, merely to signify, let alone to signify one thing.

Any bugbear that can be completely parsed was never a monster, but some rubber-mask-wearing Scooby-Doo villain, a semiotic banality in fatuous disguise. It is a solution without a problem.

8.

Our sympathy for the monster is notorious. We weep for King Kong and the Creature from the Black Lagoon, no matter what they’ve done. We root for Lucifer and ache for Grendel.

It is a trace of skepticism that the given order is a desideratum that lies behind our tears for its antagonists, our troubled empathy with the invader of Hrothgar’s hall.

9.

Such sympathy for the monster is a known factor, a small problem, a minor complication for those who, in drab reaction, deploy an accusation of monstrousness against designated social enemies.

10.

When those same powers who enmonster their scapegoats reach a tipping point, a critical mass, of political ire, they abruptly and with bullying swagger enmonster themselves. The shock troops of reaction embrace their own supposed monstrousness. (From this investment emerged, for example, the Nazi Werwolf program.) Such are by far more dreadful than any monster because, their own aggrandizements notwithstanding, they are not monsters. They are more banal and more evil.

11.

The saw that We Have Seen the Real Monsters and They Are Us is neither revelation, nor clever, nor interesting, nor true. It is a betrayal of the monstrous, and of humanity.

#china mieville#theses on monsters#posting bc i couldnt see it anywhere and im on a real china mieville kick#love this little poem

630 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I know I haven't said much (anything?) on Gaiman/Mieville/Munro, but here's my take as a bookseller who has been a bookseller for goddamned too many years:

For the question of "what do I do when I find out that a work that was transformative to me was written by an abuser?" you have to realize that having loved their work is not a reflection on you– abusers can and very often do make art that speaks to us. They are also exceptionally good at having a charming public face, knowing the right words to say, and knowing how to present themselves to endear themselves to a specific audience. Parasocial relationship or not (and I think there's something interesting to be noted that Gaiman was extremely online and Mieville (afaik) had no social media presence), it's not the fault of the fan that they didn't know that their favorite is an abuser.

That said, if you continue to support their work knowing what we know now, I'm giving you a hard fucking side eye.

Here's the depressing part: you can't know if an author is an abuser based on their works or their public persona. My advice to you as someone with goddamned too many years in books?

Read midlist authors. Stop reading bestselling authors and authors who are the darling of their particular genre. Read authors who likely will not sell their work for adaptations or have celebrity coauthors or are invited to teach a semester of literature at [expensive private college full of kids from Long Island].

Read widely, even within your preferred genre. Not only will you expose yourself to so much brilliance, but if a fav is outed as a gross abuser, it's far less difficult to move on.

As a subset of 2: Try try try to develop more than one favorite. Find authors whose works you will read sight-unseen (as I'm sure many of you did with Gaiman), but have a stable of them. (I, for instance, have five authors I will pick up whatever they write, no questions asked.)

Stop relying on cis/het white authors. Read queer authors. Read books by people of color. Fall in love with those books!

This is, of course, not a surefire way to avoid supporting abusers– there is no way to do that. But expanding your reading will have nothing but positives for you and positives for the authors that you read.

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whoa dudes.... just met Keanu! 😎😊🥳

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keanu Reeves teamed up with China Mieville, one of the greatest living authors of the New Weird movement, to write a novel about his edgy self-insert OC who’s an 80,000 year old immortal warrior who was born because his mom fucked lightning. Cringe culture is dead and John Wick himself killed it. Write your goddamn stories and don’t let anyone tell you they’re cringe.

#the book of elsewhere#Keanu Reeves#china mieville#writing#writing advice#writing inspiration#cringe culture#reading#books#literature

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

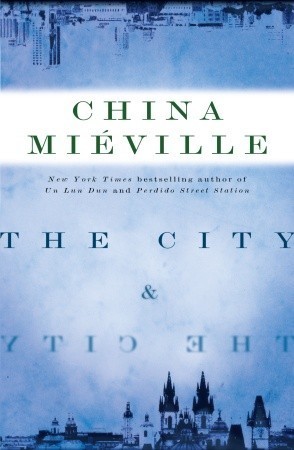

2024 Book Review #71 – The City and the City by China Mieville

Mieville is one of those authors whose influence and artistic shadow I’m far more familiar with than the guy himself or his actual work. I read Perdido Street Station years and years ago (quite good, not as clever as it thinks it is and has let’s say Issues with gender, I would have been better served reading it without knowing all the hype) and I got about halfway into Railsea at some point in university (a great central aesthetic and cute conceit sadly does not sustain an entire book of otherwise uninspired pastiche), and otherwise? I’ve just read and enjoyed far more stuff that cites him as an inspiration or is writing in the whole New Weird tradition (name now at least a decade out of date) that he was one of the big names establishing. So this is me doing a bit to rectify that imbalance, and also trying to fail a bit less comically at my literary fiction reading goal before the year ends. It served both ends neatly, and as a bonus was even a pretty decent read.

Tyador Borlu is a detective of the Extreme Crime Squad in the vaguely Balkan city-state of Beszel who, as detectives in novels inevitably due, gets himself hopelessly entangled in the case of a young woman murdered under murky and improbable circumstances. The investigation leads inevitably to the conclusion no one wants to deal with – that this is a cross-border case, and that Tyador will need to chase the trail of corruption and conspiracy into the neighbouring and overlapping city of Ul Quoma. Only by working with officers from both the mirrored cities police forces is there any hope at all to get to the truth beyond all the hints of a secret conspiracy pulling the strings of both and murdering to cover its tracks.

Which is to say, this is a fairly standard detective story plot that often seems there mostly to explore, poke at, and examine the implications of the lovingly detailed high concept setting. Beszel and Ul Qoma are the true stars of the show here – two cities with their own languages, cultures, histories and governments, even their own borders and economic trajectories, that by odd coincidence happen to cover the same geographical area. A Beszel street might run along an Ul Qoman park, and but every driver on it would simply unsee the families enjoying themselves walking or playing in it. They do not notice the rattling of a train in a another city merely because it happens to run directly above their apartment – or if they do, they’re trained and educated since birth to show absolutely no sign of it. The two cities are separate and foreign to each other, no matter the fact that their residents walk by each other on busy streets every day. This is enforced by popular agreement, by centuries of tradition and, n a pinch, by Breach – the shadowy and opaque secret police empowered and respected by the authorities of both cities as an independent and almost occult boogeyman, there to keep the two nations firmly separated from each other.

Which is an absurd and fantastical a premise as any of Mieville’s other books on the face of it, but he really has put in the work here. The cultures of the two cities both seem real and distinct, and painstacking care has been taken figuring out exactly how all this would work day-to-day with mid-2000s technology. It’s still asking for some heavy suspension of disbelief, to be sure – but once you accept the premise the book never does anything to really throw you out of it with egregious implausibility. If everyone wanted things to work like they’re presented as, if feels like they probably could – and the ways they couldn’t are each acknowledged and given some level of justification or another (or, if not, made into whole plot points).

So yes, this is a very Theme-First novel. It’s never really didactic, and one absolutely never gets the sense of Mieville getting up on a soapbox to lecture at you, but then he really doesn’t have to. The setting makes the point about nationalism – about how lethally hard and sharp borders that exist only in the human mind can be – quite clearly without too much elaboration. Which is really my preference for getting these things across.

In the interview at the end of the book that I very lightly skimmed through, Mieville calls this fundamentally a crime novel more than anything else, which feels difficult to disagree with. It’s honestly kind of fascinating to see his politics – which generally come through quite loud and clear. Read Perdido Street Station and then take one guess what stance his history of the Russian Revolution takes – get absolutely buried under the expectations and requirements of a hardboiled police mystery. There’s still the same cynicism towards political establishments and assumption of corruption as always, but it’s frankly weird to read the avowed Trotskyite write a story where the happy ending is the protagonist is recruited into the secret police. Or just all the blase matter-of-fact narration about the use and usefulness of beating prisoners, informants providing private records on demand, a general surveillance state, and so on. It’s all of a piece with the rest of the genre’s trappings, of course – the general cynical view of the world, the fact that the most personally admirable character is the girl whose already dead on page 1, and the fact that the books central relationships are three different iterations of the natural and sacred bond between a cop and his partner. The genre emulation is really pretty note-perfect, and I’m not quite sure if this is good in terms of getting out of the way and letting the themes and setting taking centre stage or if it ends up muddling and confusing them.

It does save the book from the very common failure state of setting-heavy novels that end up feeling like tourism brochures, at least.

Truthfully the most interesting part of reading this for me was how the ~15 years since publication have left it feeling like a bit of a period piece. The whole vibe of the book and the Europe it presents is just incredibly mid-aughts in ways both obvious and hard to explain. The Twin Cities themselves, of course – the whole conceit obviously owes a lot to the collapse of Yugoslavia and the wars that followed (the talk about the difference between the cities’ languages feels like it was taken 1:1 from people talking about Serbian and Croatian), with more than a dash of divided Berlin in inspiratio n (it seems less than accidental than the more Western and pro-American Beczel has a much more Germanic vocabulary for things whereas Ul Qoma is a melange of Slavic and Turkish). There is, throughout the book, a sense that these carefully and lovingly maintained divisions between cities and peoples are an anachronism, a rough spot that cannot long withstand being smoothed out by the homogenizing tides of globalization and the convenience of international commerce. More directly – the backdrop to the plot is the economic boom a former Eastern Bloc state is going through since opening itself up enthusiastically to foreign (western) investment, and the plot itself involves a corrupt conspiracy between a pro-business Social Democrat, an American tech company, and the easily duped ultranationalist thugs as muscle. It all speaks so deeply to the assumptions and trends of the world that hadn’t quite shaken off the hangover of the Cold War and for which the Great Financial Crisis was still over the horizon.

Even the book’s portrayal of politics has this feel. The vaguely-alt-left Unificationists and the assorted far-right ultranationalists are all portrayed as hopeless lost-causers; potentially dangerous (more the latter than the former) and useful tools in the hands of those who know what they’re doing, but on their own nothing but bitter old men and deluded kids who refuse to accept how the world works – radicals who the real powers leave be because they have infiltrators in every group, and anyway if they ever had a chance of success they’d be rolled up before they even realized it. Real power is the chamber of commerce and the established parties, the police apparatus and foreign corporations – the avatars and defenders of capital and the status quo. Even the plot itself – the revelation that the secret conspiracy which might overthrow everyone’s understanding of their history and their nations is just a smuggling operation that’s gotten out of control preying on the naivete and idealism of a young genius – feels so very End of History. It’s kind of charming, really.

Anyway yes – enjoyable read. Never really set me on fire and nothing about it has really gotten stuck in my head? But glad I read it, and have no real complaints about doing so.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reeves tends not to get involved in politics. When I ask how he’s feeling about the US election, he responds, “God bless democracy” – to which Miéville says, “I can’t wait to see the beginning of democracy in America”.

“I think it’s fantastic,” Reeves continues. “And I think it’s really great – illusion or not – that people can cast a ballot… I’m just glad there’s an election and people get to make some kind of choice.”

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Loads of children read books about dinosaurs, underwater monsters, dragons, witches, aliens, and robots. Essentially, the people who read SF, fantasy and horror haven't grown out of enjoying the strange and weird.” ― China Miéville.

#booklr#books#bookblr#fiction#book#quotes#book quotes#quotations#quote#book quote#china mieville#fantasy#scifi

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

#prose#typography#dark academia#poem#rainer maria rilke#rilke#r. m. rilke#writing#words#quote#keanu reeves#the book of elsewhere#china mieville#poetry#poem quotes

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

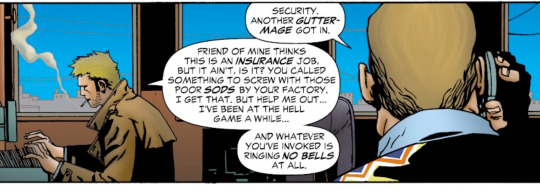

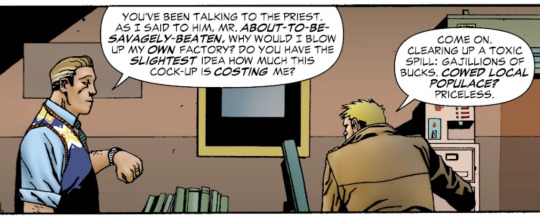

I need China Miéville to write more Hellblazer stories, because that short one in the christmas special of original Vertigo run (250) wasnt enough .. like..Miéville had John figured out and his way of writing urban fantasy would work perfectly.

Perfect.

(*tho it would be so much better if it wasnt colored by Jamie Grant n Stefano Landini.. why would you do this to lineart like this...its so painful to look at..)

#china mieville#hellblazer#john constantine#thoughts#comics#every time comic is colored by stefano landini or jamie grant i loose a bit of my life#n it going through print doesnt help it#smooth n greasy with bland colors#ughhh#i was so happy when i remembered mieville hellblazer n then boom#stefano landini#jamie grant#...#anyway anyway.....i love when hellblazer writers make john very lame

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading “Perdido Street Station” rn and the world building is fantastic.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Spanish Dancer” from China Mieville’s Embassytown

Not to overstate things but I would die for them

#embassytown#china mieville#this is my art#fan art#spanish dancer#alien#xenobiology#aliens#character design#this is my emotional support alien crab coral horse

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slake Moth

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

neone reading the book of elsewhere?

keanu narrates at least the first chapter, its pretty dope...

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Literary” speculative fiction reading list

A list of recommended sci-fi and fantasy books with high-quality prose and serious or complex themes, including works by Le Guin, Wolfe, Delany, Miéville, and Banks. This selection is drawn from a much longer list of well-written and ambitious SF that I published on my website.

#book recs#book recommendations#book reccs#reading list#book list#speculative fiction#science fiction#fantasy#sci fi and fantasy#le guin#china mieville#iain banks#gene wolfe#samuel r. delany#literary#literature

197 notes

·

View notes